'Distribution, Redistribution or Maintaining the Status Quo? The Normative Foundations of Intimate Partner Constructive Trusts'

Judgments concerning intimate partner constructive trusts often claim not to effect a redistribution of property as between the legal and beneficial owners. Yet despite looking at the parties’ respective contributions and the context of their relationship, the courts’ findings embody assumptions about justice and the value of labor within marriage-like relationships. Therefore in finding a constructive trust and determining the date at which it arose, it is at least arguable that the courts are themselves allocating property interests. This paper examines key Australian decisions on intimate partner constructive trusts to identify and critique possible justificatory norms on which contemporary doctrine in this area is founded.

This paper is part of a larger project: my PhD research which is a feminist analysis of equitable proprietary interests in intimate partner constructive trusts. The focus of this presentation is property - rather than the other remedies available in the context of applications for declaration of a constructive trust (such as an account of profits, or a trust over sale proceeds). Property is valorised in our system. It offers security against third parties, the opportunity for capital gain and a right of possession - particularly important when there is a home at stake.

The Courts claim that they do not redistribute property ie they find existing property. But this assumes a particular way of understanding property - resting on a normative foundation that I will explain below. A finding of property in turn reinforces this norm. My question though is whether the underlying norms represent a valid understanding of property within this context of intimate relationships.

The Courts are very clear that they do not effect a redistribution of property. Interestingly though, in finding a constructive trust, a beneficial proprietary interest, they will take into account third party interests. So the 'finding' of a proprietary interest in favour of the applicant is dependent on there being no subsequent competing interests. And courts have the discretion to declare the interest in existence either from the date of the acquisition of the legal estate or from a later date, such as the date of judgment. Such an order will result in a forfeit of any security implicit in a proprietary interest. If the property already existed, it is difficult to see why a third party interest is relevant to the finding of property in the first place.

My other initial observation is that I believe the view of property and its embedded norms is gendered. In this 1970 decision for example, the UK Courts were still interpreting the Married Women's Property Act (of the late 19th century). Implicit in this statement is an acceptance of the primacy of the husband's estate - it presupposes that the husband's interest is valid. It seeks to bring the exercise of judicial discretion within an existing normative order. More about this below.

All of this is premised on the primacy of the legal estate - the fact remains though that the equitable proprietary interest subsists lurking below the surface of the legal estate; and, within the same normative framework.

The claims over legal and equitable estates are in tension - perhaps in every case except that of an express trust - but this would usually be resolved via the priorities rules. Not so in the case of the beneficial interest pursuant to a constructive trust, which is itself carved out of the existing legal estate. The two estates on the one hand are presumed to occur within the same framework, yet on the other hand, the equitable estate is found as a consequence of the application of court discretion.

What is it then that renders the legal estate preferable? What underpins its primacy? In the Torrens system, the principles of transparency, efficiency and certainty would be cited as justifying its paramountcy. These are effectively economic reasons but these are based in turn on the transparency of the deliberative action or intention of the transferor.

In contrast, the equitable estate is opaque, discretionary and retrospective - as though there is someone behind a curtain pulling the levers... Yet hte judgments represent the equitable interest as part of hte same normative system as the legal estate. This is central not just to our legal system, but a reflection of the derivation of our political and economic system and our very conceptualisation of the citizen as individual.

I draw on the ideas of the Enlightenment social contract theorists who clearly associate the individual with property. Property itself is an extension of the self and a measure of personhood. Indeed one's status as property owner is likewise connected to citizenship. Notably also, property owner/individual/citizen is a man. And to the extent that representations of property ownership occur with a social context, that context is the marketplace. They do not occur within the family which occurs within the private sphere, beyond the writ of the law. The family's own interest is in a sense collective yet individual. Its interest is represented within the public sphere (including the market) by the man of the house.

The social contract theorists developed an account of the legitimacy of government itself out of the need for protection of property. It was by a theoretical compact that individual power was ceded to government for the purpose of upholding one's own property interests. These were individual interests, pitted against all other (competitive) individuals.

And so these political principles are embedded within our law - both public law, protecting the individual from the excesses of the state (reinforcing the primacy of the individual over the collective) and through private law where one's personhood is upheld through recognition and protection of promises - free will - and individual property rights.

In turn, the law of constructive trusts embodies or interprets these ideals through its approach to determining a proprietary interest. These reinforce individual interests that are in competition with each other. They uphold our own individuality and autonomy in the liberal sense of an isolated, atomistic being whose property is an extension of self; as well as a connection with the world of the citizen and the market.

Through these devices, equity validates 'interference' in the legal estate using the familiar tools of liberalism - equity is not so much an exception to the system as part of the system, embodying its norms. This is how it justifies the 'allocation' of property as a distribution, not a redistribution. In other words, it supports the status quo.

But all this rests upon an assumption that these liberal principles are valid; that they represent the reality of property. I suggest however that they are made for a different context, not for the intimate relations of the home; and that they embody a way of relating at odds with this context. On this basis, I question the courts' conclusion about distribution. Because I do not accept the underlying premise.

In the first place, the liberal conceptualisation of property is a masculine one. Excluded from the (constructed) social contract, women were subsumed into the identity of their husbands and likewise so was their property. Remember: property was an extension of the individual and their very personhood. Women didn't feature either way. There is little history - precedent - of property for the married woman (or I argue also by extension, for the woman in the marriage-like relationship). For the hard questions, it has been said, the courts have recourse to the traditional liberal tools. So too have the courts of equity in grappling with the issue of (married) women's property.

So while the intimate partner constructive trust forms its own particular subset of this area of law, the underpinning principles that justify a finding of a proprietary interest are those of the market. As lawyers who understand property law as a representation of exclusion of others from our personal domain; as an exchange of value to increase our estate value, we seek the indicia of a market transaction to justify the property. And we ignore the alternative context of property within the intimate relationship.

Even though the courts recognise the unreality of their own conceptions of intentions to create proprietary interests, they still use the standard of the rational market actor in ascertaining the proprietary interest of intimate partners.

As I read constructive trust decisions, I often see a different story from that proffered by the court. In Carol Gilligan's words, I hear a 'different voice' explaining the way in which the property came into the relationship - how each party related to each other and how they related to or connected with the property. The parties' intentions related not so much to a transaction of exchange for value, but were part of an interdependent relationship to create a home. The relationship may or may not have involved merged finances, but the intention that infused the parties' actions was relational. Such an alternative reading may expose the context for decisions; the effect of power on decisions and the varied contributions to making the home.

I explore here two early Australian decisions: Muschinski v Dodds and Baumgartner v Baumgartner. I hope to demonstrate the primacy of liberal reasoning by the courts, and also expose the 'different voice' of the applicant women.

All of these issues were relevant to the experiences of the applicants in terms of their relationship with the defendants, with the property and in decisions they made about the application of their labours, their energy and their finances. Yet none of these issues is relevant in the application of property law - they do not reflect the norms of property and to take them into account, for the courts, would amount to an illegitimate interference with the existing legal estate: a redistribution of property.

It's on this basis that I suggest that the norms of property law obviously serve the status quo - they support a competitive individualistic bidding for an enlarged and exclusive estate. But they have no capacity to recognise the investment made in pursuit of personal relationships.

For the concern of liberalism lies not with women, or the home - or personal relationships. The institution of property and the laws that support it operate on a different plane. So I finish this paper with a question. I ask how might we reconceptualise the idea of property to include the experiences and concerns of those whose estates, labours and energies exist outside the market?

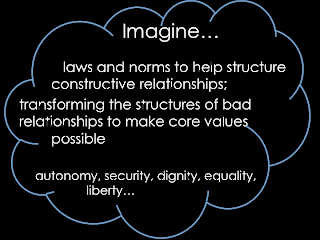

Jennifer Nedelsky proposes a relational approach to law. She rejects the individualism of liberal equality as it positions the lone self as primary. Instead, she asks how law might support autonomy through our experiences of relationships. Not only intimate ones, but more broadly and including with and through institutions (such as property). Constructive trusts and property generally with their focus on exclusion and possession as dominion, fail to promote ideals of autonomy, security and dignity as articulated by Nedelsky. I argue that this is particularly the case for many women within marriage-like relationships who work towards their relationship losing financial resources and thereby their autonomy.

On this basis, it is time for systemic change. Property is after all just one institution amongst many - socially, legally, economically - that position women disadvantageously. Together they inhibit women's full and equal engagement in society. The chimera of the courts' "distribution" of property in constructive turst cases is only a small part of the widespread change that is called for.

Thanks for this, an interesting discussion and entertaining pictures :-)

ReplyDeleteIt would be interesting to explore how this issue of the "construction/definition" of the existence of a constructive trust out of the application of a legal process fits within the context an alternative legal process that is designed to alter, rather than simply define property interests. I am of course referring to property settlement proceedings in the Family Court.

This is particularly interesting at a time when the High Court (in Stanford v Stanford) has emphasised the need to establish the legal AND equitable interests of the parties before deciding whether it would be just and equitable to make any orders altering them....

If in each case the Family Court were required as a preliminary step to consider whether there was a constructive trust in place between the parties and THEN as a secondary step decide whether it would be just to alter the allocation of property as determined under that law, we might get some very different outcomes.

As you point out, the principles applied to the question of whether a constructive trust exists are "transactional" rather than "relational". The principles applied by the family court to determine a parties' interests in property are designed to focus on the aspects of the relationship as a whole; the opposite approach.

It may be that your call for reform to a more relational approach is slipping further away, if even the Family Court is now being called on to take a strict approach to determining legal and equitable interests prior to allowing for any "relationship" factors to get in the way.